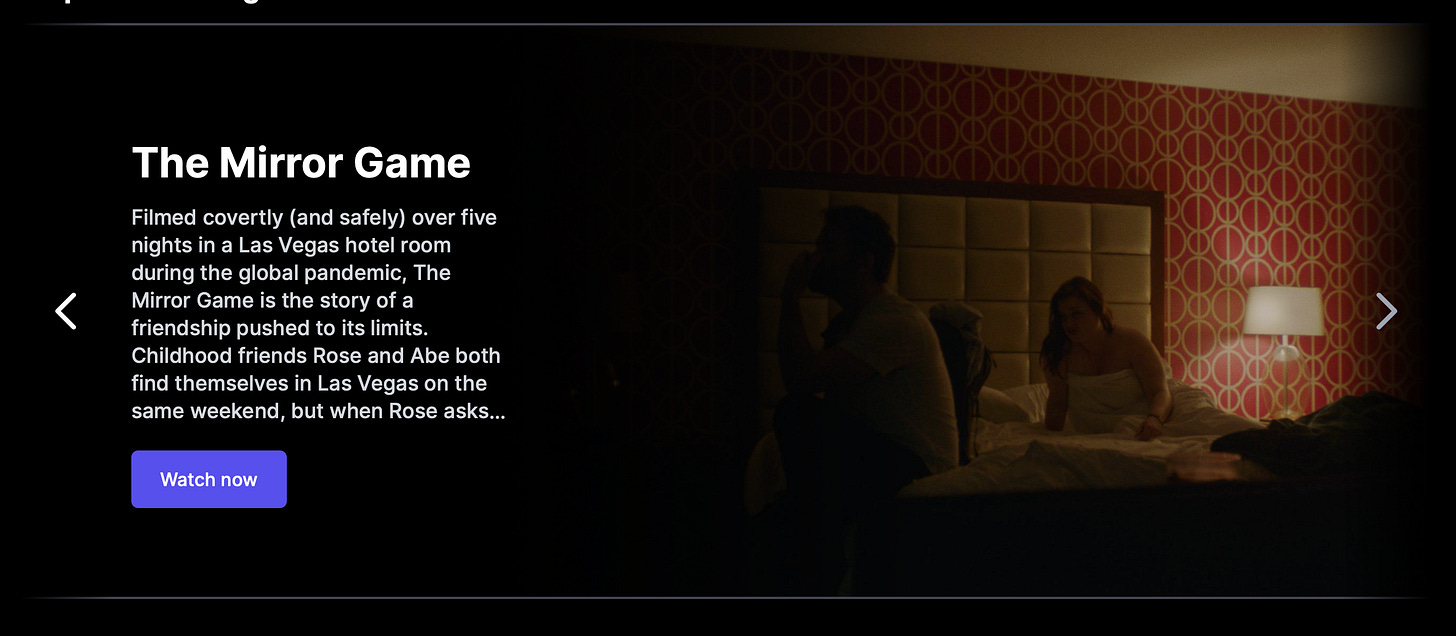

Before we begin, a little business: The Mirror Game is now available to watch online via the Portland Film Festival. Tickets are required. Streaming there will continue through November 26th! So if you want to see this movie I wrote but haven’t yet, now is your chance.

Last weekend, I found myself on a quick trip to Bowling Green, Kentucky for the wedding of one of my grad school classmates. My traveling companion, Katie (another one of our screenwriting cohort) and I got situated at our hotel on Friday night, but the wedding didn’t start until 4:30 on Saturday. So we had some time to explore. What does one do on a brisk, sunny Saturday in Bowling Green? We took our hosts’ advice and bought two seats on a boat tour of a local cave. The Lost River Cave, it’s called.

The cave’s website predicted a short, informative walk and a twenty-five minute boat ride. We had to sign a safety waiver acknowledging the dangers of the trek. But the dangers were few — a capsized boat would have dumped us into just three feet of water. A more harrowing element of the journey came just after we pushed away from the modest dock. We were all asked to fold our heads down toward our laps, emergency landing style, to avoid hitting our heads on a twenty-foot stretch of low rock at the cave’s mouth. The tour guides had dubbed this “the Wishing Rock” (because if you didn’t keep your head down until you were given the all-clear, you’d “wish” you had).

Once we were allowed to lift our heads and sit up straight, the only thing scary about the cave was the fearsome power of nature…and perhaps the pitch-black chasm of time itself. The cave walls and ceiling had been shaped by repeated massive flooding; the mineral deposits that decorated the cave had been built up by micrometers per century.

While the history of Lost River Cave was written all around us on a geologic scale, I was fascinated by what we learned about its human-scale history. While we couldn’t see them from the boat, we were told of artifacts — both from Indigenous people and from Civil War soldiers who used the cave at various times in history and left evidence of their lives and work. We were told of the many failed, variously disastrous attempts to use the cave as a mill or distillery. We were repeatedly reminded of its past life as both a hideout for Jesse James and the site of a 10¢ Wax Figure Jesse James Tour.1

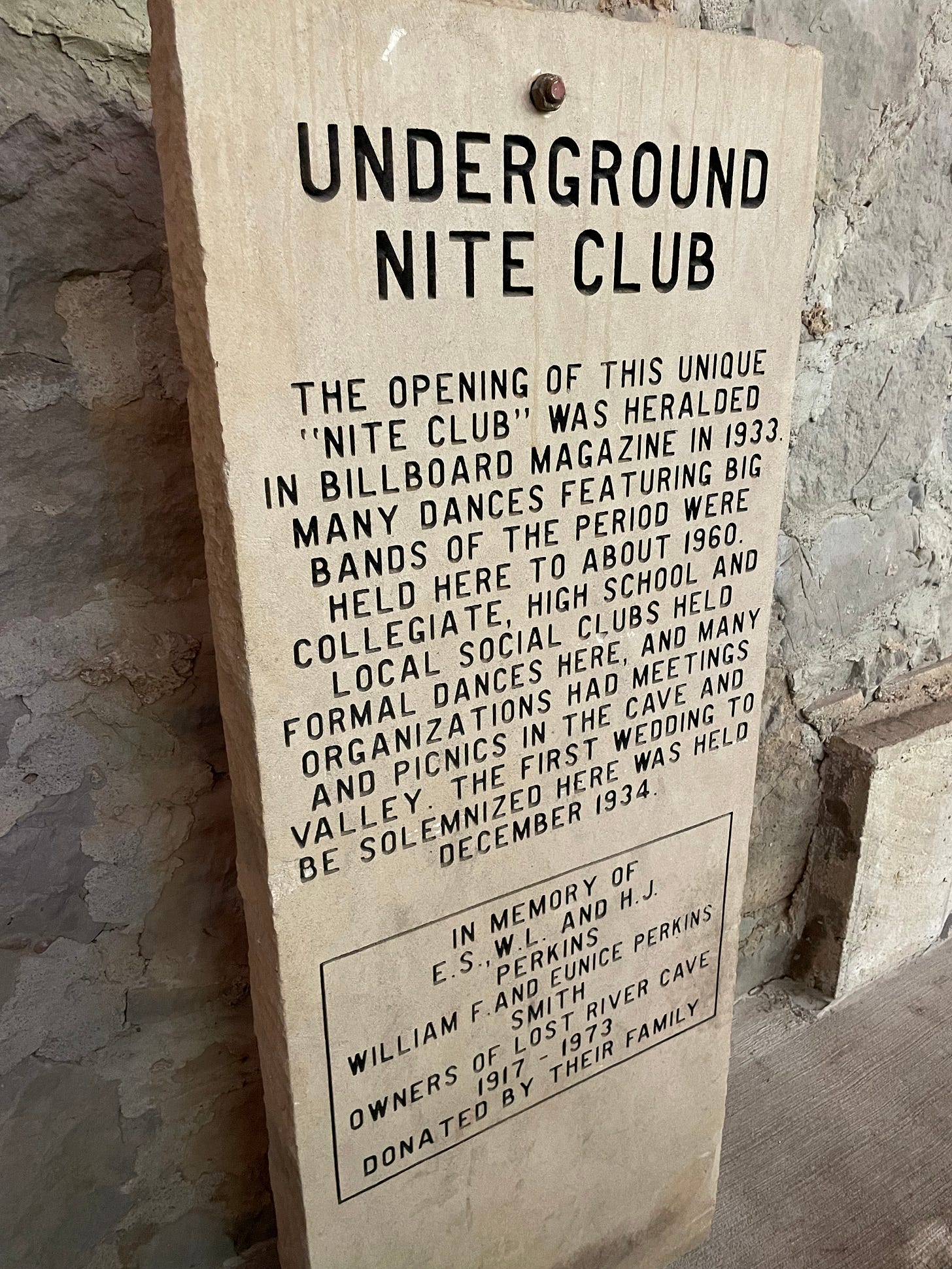

Especially remarkable was the “night club” area just outside the cave. It was built in the 1930s as a literal night club, a bandstand platform on the water that took advantage of the cool air constantly blowing from deep within the cave, even on hot summer nights. On this Saturday afternoon, it was all set for a wedding reception (not the one I was in town for) and our tour guide had to ask a wedding DJ to hold his soundcheck until tours were done for the day.

But for much of the 20th century — yes, during your lifetime, most likely — the cave became little more than a dumping ground. It was treated like a black hole for trash, and from the outside, operated to much the same effect. Stuff got sucked inside and forgotten. No tours of the cave were offered during that era, but apparently they would have been pretty gross. In a few decades time, some 80 tons of trash accumulated inside the cave.

Before our tour began, Katie and I had waited on a bench for about twenty minutes. It was a beautiful day, and this now-Californian Midwesterner was happy just to be wearing a jacket; on top of that, to be surrounded by a canopy of lush, transforming leaves? I was positively overjoyed. Acres of public park land surround the cave, and people were walking their dogs, running their kids, pushing strollers.

It’s sad and frustrating to think of people not taking care of that cave, and of the picturesque land around it. But happily — miraculously? inevitably? astonishingly? — the story didn’t stop there. The land was donated; a huge volunteer effort ensued; the park as it currently exists was opened.

Civil War soldiers chilling in the cave left their names and battalions in markings on the wall. Did they intend for them to be found over a century later, or were they just leaving their mark for the next guys who passed through? I bet that when Jesse James and his gang were hiding out in the cave, they never imagined that people would pay a dime to see them there as wax figures. I doubt the nightclub patrons could even imagine the club going bust, much less electronic speakers bouncing electronic music off the outer walls of their cave. The soul who tossed their old mattress into the cave probably didn’t think, “people will clean this up eventually.”

For humans, not thinking on a generational scale can lead us to do some pretty stupid stuff. It can also render unfathomable the possibility that a change for the better might be in the cards. That we humans might have the power to make that change.

Our tour guide, Matt, cracked a lot of wry, straight-faced jokes during the tour. One of them was about how it took eight years of volunteering to get the cave in shape. “Have you ever tried volunteering for a day? Now try to imagine how long eight years of that would feel!” Those eight years began in about 1990. We met a guest at the wedding that night who told us that she’d visited the cave in elementary school, but her class hadn’t been able to go beyond the Wishing Rock. And now, a couple decades later, our tour was so full on a Saturday afternoon that they had to add a second boat.

The story doesn’t end there, of course. Time marches on, and it will take continued effort and organization to keep the cave and park in good shape. Who knows what changes nature might bring? In fact, while we were in the cave, Matt pointed out a relatively dry mineral formation where a waterfall had once flowed — you could tell by its shape. Then a paved freeway had been built above the cave, and the road had filled in any little cracks and crevices where the water had been seeping in to form the now-dead waterfall. And yet, he added, some droplets of water have begun to appear again. He said they have some hope that the waterfall might come back.

Did he mean in our human time, or in geological time? I forgot to ask.

Reminders were both verbal and visual — a now-unused set of stairs between rock formations; some not-quite-rinsed-away lettering on the outside of the cave; a wrought iron gate that resembled a jail cell.

https://youtu.be/wPTIOP7hO2A