Choosing the Same Nuts

For the first time since I moved to California, I’m back in the Midwest for Thanksgiving, first spending a brief interlude in Chicago before heading to St. Louis for the main event. That also makes this the first time I’ve been in Chicago in the winter1 since 2018, and boy did I pick an eventful few days to spend. On Friday, the tree in Millennium Park was lit. On Saturday, Mickey Mouse helmed the annual lighting of the lights along Michigan Avenue. My dad and I didn’t attend either of these events (though we took in the lights once the celebratory lighting had been done). Instead, we engaged in a slightly more mundane and less seasonal ritual, the ritual that accompanies any visit to my dad: we went to the grocery stores.

My first morning here, we walked to Trader Joe’s. Well, first we walked to Whole Foods, then we stopped briefly at home, THEN we walked to Trader Joe’s. For both my dad and I, one big day-to-day advantage of Covid-adjusted society is the freedom to go to the grocery store at whim.2

Trader Joe’s devotees will know that the store always has a display of new items on a shelf somewhere in the store. In Silver Lake in LA, it’s right by the entrance; at 3rd & Fairfax, it’s in the far back corner; and in River North, Chicago, the shelf is an endcap in the center aisle, facing the rear of the store. On Friday, perusing this shelf, I locked eyes with a green bag of mixed nuts. Well, technically, any eye-locking was all on my side of things, as a bag of nuts doesn’t have eyes, but I digress. I picked up the bag3 and took it to the dairy case where my father stood with his half-cart. I said something kind of unusual for a 38-year-old woman to ask her father: “Can we get these?”

As soon as the words came out of my mouth, I felt the way they were both natural and unnatural, and was struck by the pleasant sense (missing from any childhood utterance of such a phrase) that if I wanted the nuts I could just buy them myself. But no matter. Without really looking at the bag or considering what he was agreeing to, my dad assented and continued scrutinizing the cheeses.

Not more than five minutes later, he pushed his cart past that same excellent display of new products. He looked at everything on the shelf — Italian cracker mix, peppermint pretzels, autumn spice coffee beans — and, finally, he grabbed a green bag of Olive & Herbs Mixed Nuts and put it in the cart. “Let’s get some of these,” he muttered.

My dad didn’t notice (but I did) that he’d placed the bag of nuts directly in front of the identical bag of nuts I’d added to the cart minutes beforehand. I laughed — at him? Sure, a little bit, at how little attention he’d paid to the rogue item I’d so gingerly requested, and then felt silly for requesting in that way. I also laughed with him, though he didn’t fully appreciate the joke as he hadn’t watched it unfold like I had. But mostly I was laughing because it was…one of those things. Those me-and-my-dad things that amuse, surprise, and frustrate me, depending on the context.

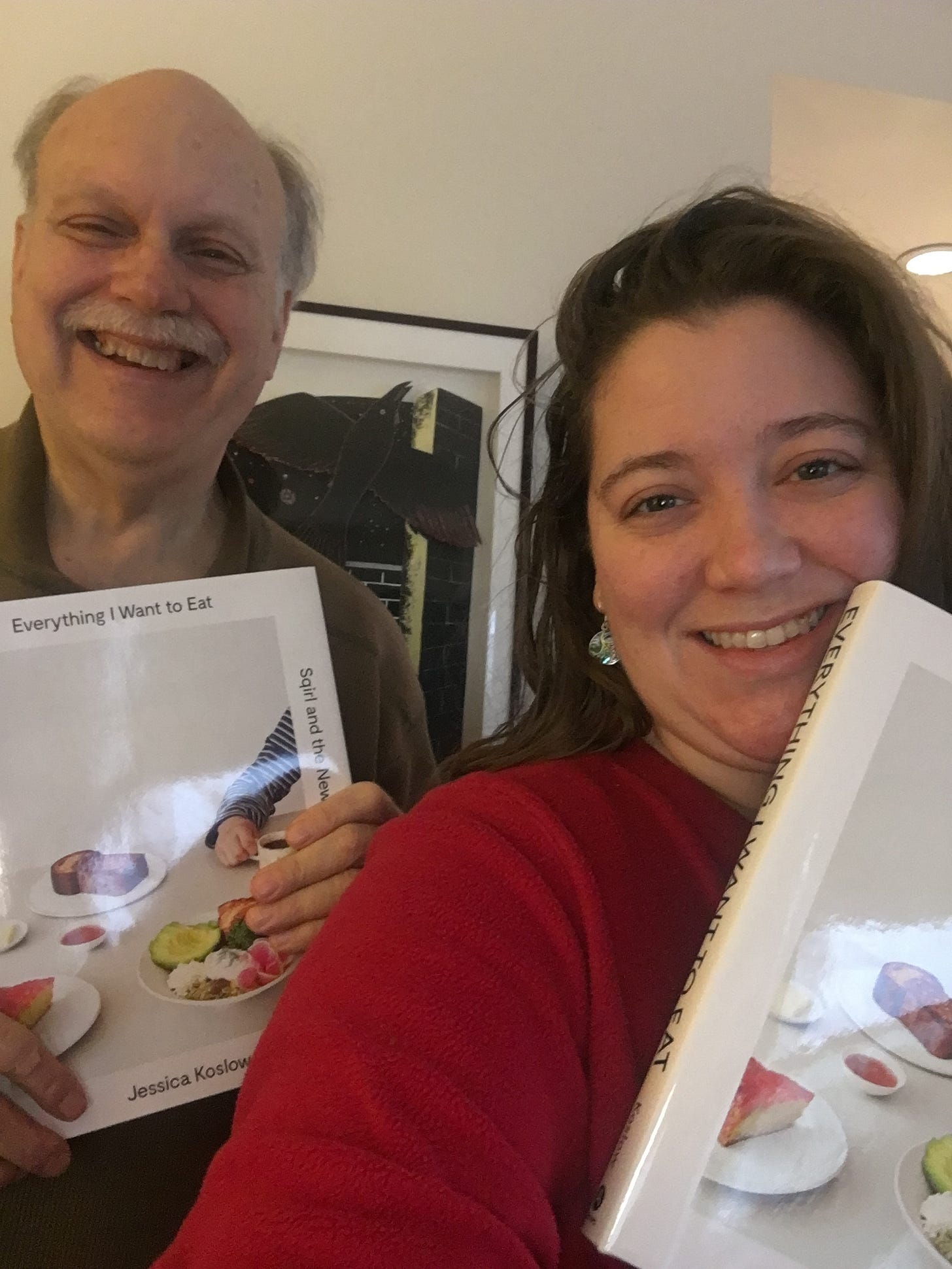

A few years ago at Christmas, my dad and I bought each other the same cookbook for Christmas. We had not discussed the cookbook beforehand. That was an amusing surprise. Sometimes, I catch myself saying something or gesturing or articulating in a way that is classically “my dad.” That, unaccountably, I find frustrating.

Perhaps it’s because the cookbook example (as with choosing the nuts) feels like matter of shared tastes and interests, cultivated over a lifetime. The gestures and facial expressions, on the other hand, seem to have cropped up on their own, in the years we have lived thousands of miles apart. They feel like something that is outside of my control — a sentence that my mind can’t help but form in that particular way, a facial expression that my brain was preprogrammed to adopt.

This is where I find myself at this juncture in my adult life. Asking for permission that I know I already have. Inextricably tangled up in the mystery of what parts of myself are my own, which were taught to me, and which are in my DNA.

It’s funny, because I’ve also been seeing (and engaging with) some content about parenting lately. The thesis statement that keeps entering my field of vision is this: your kids are not you, and having children means entering into relationship with a stranger. I don’t have kids of my own yet, but there are kids in my life. Real, flesh and blood kids, and the vaguely imagined future kids that have been a part of my fantasy life since I was a kid myself. When I hear parenting advice, I relate to it through both of those lenses, and also a third lens: my own kid-hood. We are all the children of parents of one kind or another. What insights does newly received wisdom about parenthood offer to our lives as former children? And if there’s no guarantee that children and parents will have much in common, what does it mean to reach for the same snack at the grocery store? How much of that is cultivated, and how much is in-born? Do we have jurisdiction over any of it, either as parents or as children?

My own situation is a unique case study here, as I have a particularly strong relationship with my father. And he is a universally well-liked person. There are many ways in which we are different, but it’s hard to feel too bad about any of the ways in which we’re the same (outside of that frustration over the ways in which the sameness feels outside my own control). Meanwhile, I have been told from my earliest teen years how much I am like my mother, but I have no way of evaluating those similarities in real time. I was fifteen when she died. Already, I was frequently mistaken for her on the phone. At nineteen, old family friends at my grandfather’s funeral noted how I moved like her, something I’d have no way of knowing on my own. Looking in the mirror as I get older, I admit I see her there more and more. But as for any other ways that we are alike, the only person who can really tell me — the only person who is likely to see or hear enough of me to notice — is my dad.

Following quickly on that line of thought is a dangerous question: who would I be if she’d been around for longer? Would my dad and I be choosing the same nuts at Trader Joe’s? Or, deprived of the tragedy that forced us to lean so firmly into one another, would I be someone with different snack tastes entirely? Maybe I’d have reached for the Peppermint Pretzel Slims. Would I even recognize that person?!

Now I’ve written us into a bittersweet, impossible place, so let’s come back up for air. It’s a holiday week, after all. Some levity, please.

We came back to my dad’s place, and he was keen to transfer the bag of nuts into a tin. As he searched for it, I asked him how we would remember that the nuts were in the tin, and, matter-of-fact, he explained that the tin he had in mind was “a nut tin.” Then he found it: a small green canister that once contained some other kind of Trader Joe’s mixed nuts, which he’d emptied, washed, and saved for just the occasion in question. He transferred the newly acquired nuts from their also-green bag to the tin. I thought this was all pretty weird, but he saved the piece de resistance for minutes later when he bid me look again. He’d cut out the part of the bag that read “Olive & Herbs Mixed Nuts” and taped it to the tin. Now we’d REALLY know what was inside.

And here it was: an act that was so quintessentially “Don Flaxbart” that I could never hope, nor fear, to match it.

I know it’s only November, but winter has definitely started in Chicago

If the food desert is the plight of many modern Americans, my dad’s Chicago apartment is in a food ocean.

“Olive and Herbs Mixed Nuts”, if you’re shopping for a holiday snack.